A Note From the Editors

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the fifth edition of The Lumen – an art & literary magazine of the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences.

As an initiative of the Medical Humanities Club, The Lumen celebrates the intersection of art, history, literature, and medicine. Amidst an environment of scientific research and clinical experience, it aims to cultivate an appreciation of the soft sciences; a seemingly niche area that perhaps should not be so obscure.

As editors and future physicians, we are not unaware of our privilege. Patients seek healthcare not only in their most vulnerable states, but in some of the most important moments of their lives. We experience birth, death, suffering, and recovery in all their humanness, and so it is only fair that we see our patients fully. Beyond a list of symptoms and ailments lie endless stories, the intricate layers of which we will only unfurl if we pay attention. This serves as a reminder of the profound importance of the humanities, which are essential to understanding the human condition.

We hope The Lumen can connect our academic experiences with our more personal ones, illuminating a diversity of voices within our community and showing that the humanities are not separate from, nor are they simply ancillaries to medicine.

In medicine and biology, a lumen, as our colleagues very well know, is the innermost part of something. A lumen may house blood or bile, may carry or absorb, may empty and fill. We at the Medical Humanities Club and The Lumen editorial board see the arts and humanities as occupying a central, luminal position in the world of medicine.

We encourage you to contribute to future editions and to explore more of our work on our website, www.lumenmag.org. Please reach out to us at utcomls.lumen@gmail.com with any feedback or thoughts—we’d love to hear from you!

Finally, we extend our deepest thanks to our contributors, who spent their precious time creating pieces that intrigue, inspire, and empower. We are grateful for the support we’ve received from mentors, faculty, and the College. We are especially thankful to Dr. Hussain, our editor-in-chief and faculty advisor, for his constant guidance, to Dr. Matus for her commitment to the medical humanities, and lastly to Dean Ali for his generous support.

The Lumen Editorial Board

Thu Nguyen, MS4

Lena Bercz, MS3

Zainab Lughmani, MS3

Jack Newman, MS2

Solee Cheon, MS2

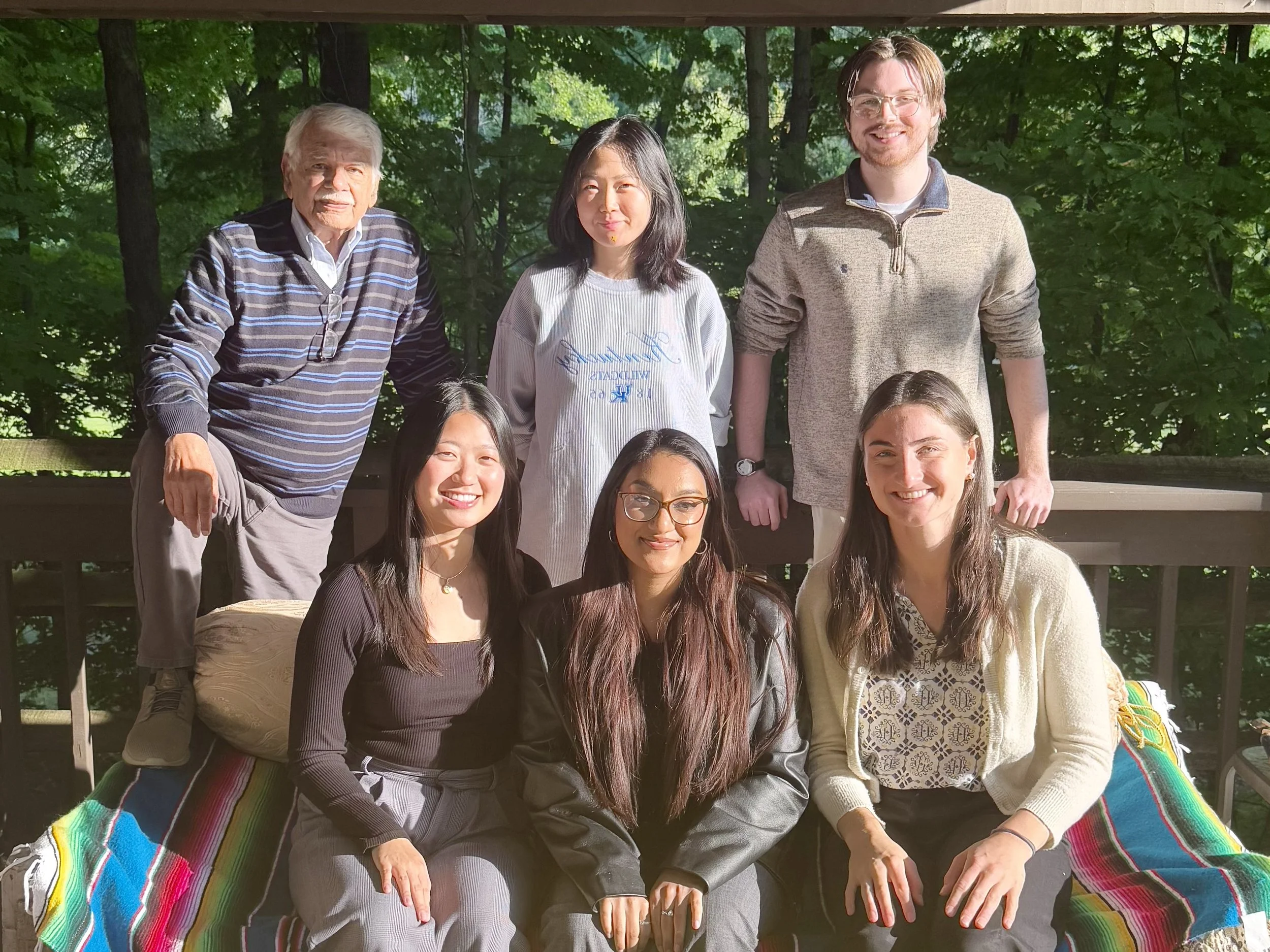

Back — Left to Right: Dr. S. Amjad Hussain, Solee Cheon, Jack Newman

Front — Left to Right: Thu Nguyen, Zainab Lughmani, Lena Bercz

Issue 005,

Fall/Winter 2025

Editor-In-Chief:

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain, MD

Editorial Board:

Thu Nguyen, MS4

Lena Bercz, MS3

Zainab Lughmani, MS3

Jack Newman, MS2

Solee Cheon, MS2

Art Consultant

Adam Levine, PhD

Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey director of the Toledo Museum of Art

The Lumen is an initiative of the Medical Humanities Club of the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences (UTCOMLS)

Cover Art: The featured cover art is derived from the original piece, “Flowers in Bloom” by Shruthi Varier, which can be found in the table of contents.

Editorial

From Dr. S. Amjad Hussain

With this issue, The Lumen is entering the 5th year of its publication. It has been a labor of love for all of us on the editorial board. We have had some difficulties initially, but those are part of any unusual enterprise, such as publishing a literary & art magazine in a science-driven institution. Despite minor hiccups, a few bright spots have been interesting and heart-warming. These constitute working with the student editors and the support of the Deans of the University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences (UTCOMLS). Dr. Christopher Cooper, on whose watch the magazine was launched, fully supported our nascent effort. And now Dr. Imran Ali, our new Dean, has been fully supportive of our efforts. Hats off to these two visionary leaders.

Since the publication of our first issue in 2021, it has become evident that our students have abundant talent as writers, poets and artists. Reviews and informal comments about the previous issues have been positive and very encouraging.

I am grateful to the student editorial board for their wonderful work in initial evaluation of contents and their constant engagement throughout the editorial, design, and printing process.

I also want to express my personal gratitude to Dr. Lloyd Jacobs, president emeritus of the University of Toledo, for acting as an advisor for poetry selection. Thanks are also due to Dr. Adam Levine, director of the Toledo Museum of Art, for his valuable assistance in evaluating and selecting submitted artwork.

Sayed Amjad Hussain

A Message from Dr. Imran Ali

I am honored and delighted to add my remarks to the fifth issue of The Lumen. The Lumen editorial board and the contributors need to be congratulated on yet another wonderful issue. Art and literature, while seemingly disparate from the science of medicine, share a common thread. Our ability to think, reason, share and create is bound inexplicably with the rigors of science. To be able to connect our emotions to our professional life defines our humanity. Physicians and scientists can learn a lot from arts and literature and the self-reflection that occurs as a result makes us better at what we do.

I am grateful to Drs. Hussain and Matus as well as the students and others who contribute to this remarkable effort. I wish all of them success and truly appreciate the importance of this endeavor.

Sincerely,

Imran Ali, MD

Dean and Vice Provost for Health Education

Professor of Neurology

University of Toledo, COMLS

Table of Contents

Think Horses, Not Zebras — by Nicholas Bunda

Dear Madam — by Meredith Citkowski

A Strange Encounter — by Julia Johnson

A Differential Diagnosis — by John Kim

Scoliosis Gallery — by Monica Wojciechowski

Thingness — by Dr. Lloyd Jacobs

Fracture Lines — by Shreyas Banerjee

The Art of Dying Well — by Luke Roberts

The Ones We Leave Behind — by Merrick Harris

Fragments from an Outbreak — by Chinenye Ezema

A Farmer’s Legacy — by Namrata Kantamneni

Giving My First Gift of Life — by Kolby Quillin

An Exercise Pill for Couch Potatoes — by Sachin Aryal

Look, Listen, Palpate — by Gabriel Bonassi, Shreya Bhoopathi, Sofia Boiajian, Tarak Davuluri, Andrew Edgington

Doctors Are Patients — by Merrick Harris

What We Stay Alive For — by John Kim

The Plan — by Namrata Kantamneni

Flowers in Bloom — by Shruthi Varier

The Choice — by Tricia Aho

False Dichotomy — by Namrata Kantamneni

How the Tables Have Turned — by Dr. Coral Matus

Octogenarian’s Song — by Dr. Lloyd Jacobs

Medicine in the Palm of Our Hands — by Nithya Sundar

Scraping the Pan for Crumbs of Pound Cake — by Dr. S. Amjad Hussain

The Eternal Flame — by Alisa Chen

Think Horses, Not Zebras

by Nicholas Bunda

He was green. For weeks, I watched Frank’s skin turn green. My father-in-law is a short, stocky man with incredible physical strength and an unmatched work ethic. As an executive for the Boy Scouts of America and a devoted husband, father, and grandfather, he never stopped moving. But recently, he was losing weight and strength. I convinced myself he was just aging. After all, nobody keeps their heroic dad-strength forever. Two years earlier, Frank had been diagnosed with colorectal adenocarcinoma. He underwent surgery and chemotherapy and, as far as we knew, was cancer-free. But as a budding physician, I couldn’t ignore the greenish hue of his skin, the weight loss, and his fading vitality. I feared the cancer had returned.

Frank was admitted to the hospital after a cardiac episode. I remained by his side for two weeks, questioning every consultant who entered the room. Cardiology thought it was atrial fibrillation; pulmonology suspected COVID-19; infectious disease pointed to bacteria; and the hospitalist suspected autoimmunity. Nobody agreed. Repeatedly, I suggested a recurrence of cancer, only to be quickly dismissed.

Each morning, I reviewed his lab results and buried myself in the literature, desperate for answers. His platelets were dangerously low, his skin mottled with red and purple blotches, and his IV sites repeatedly failed, leaving large, painful bruises. Daily transfusions of blood and platelets weren’t enough. Again, I suggested cancer. We asked for a bone marrow biopsy but were denied.

Frank had been in my life for 18 years – longer than I had lived without him. He was a second father to me. Spending every day in the hospital with him allowed me to witness the best and worst of medicine. Some physicians were patient, compassionate, and honest about their uncertainty. Others were dismissive, annoyed by questions, and confident in their misjudgment. Despite my pleas, we didn’t see his oncologist until over a week had passed. I’ll never forget the day she came. Frank, bruised and emaciated, lay silently as she swept into the room with her purse on her shoulder. “Frank, I’m sorry you’re not feeling well, but this is not cancer,” she declared before leaving just as abruptly. Fourteen days later, I held my wife as we buried her father.

In medical school, we’re taught, “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” When they eventually performed the biopsy, it revealed metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the bone marrow – findings seen in less than 2% of cases. Frank was a zebra. While earlier diagnosis wouldn’t have changed his prognosis, the delay haunts me. I still think about it every day. William Osler once said, “Listen to your patient; he is telling you the diagnosis.” I often reflect on what I owe my future patients. Will I listen? Will I consider their ideas? And when I inevitably miss a zebra, will I have the humility to face their family and own my mistakes? Frank would expect nothing less.

Photograph of Nick and Frank

Nicholas Bunda is a fourth-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

Dear Madam

As featured at the 2025 Donor Memorial Service

by Meredith Citkowski

Dear Madam,

It’s odd to think that on one hand I might

In this short time already know more about you than almost anyone

And yet I don’t even know your name.

Maybe one day I will.

Until then, I won’t call you by the number on the table

Or the tag on your toe

So, Madam will have to do.

Dear Madam,

I don’t know what you did for work

Or what your title was.

Did you have one?

I don’t know what kind of car you drove

And I don’t know what kind of clothes you wore.

Isn’t it odd?

All of the differentiators we work for

Fail to differentiate us

When we’re lying in rows

With cautious students peering down.

And anyway

Whatever you did

Or drove

Or wore

I just hope you enjoyed it all.

Dear Madam,

I find myself reflecting on your life despite not knowing anything about it.

Did your muscles tense and relax as you wiggled your toes in the sand at the beach?

What sorts of games did you play as a child?

Are these the knees you scraped, learning to ride a bike or playing on the swings?

Someone held your hand for the first time.

Who was it? A first date? Were you nervous?

Dear Madam,

I wonder what you liked to eat,

Which flowers you liked to smell,

And what kind of music you listened to.

I wonder what the world looked like through your eyes.

And when I look at your eyes, I wonder who else looked –

Not at them, like I am –

But into them like I can’t.

And what did they see?

What made them fold in laughter or swell with tears?

How many feelings, I marvel, must your eyes have reflected over the years.

Dear Madam,

It might be strange to say that the tendons of your foot are unexpectedly beautiful,

But they are.

And you’ve taught me already

To look carefully and intentionally

At things I might have taken for granted

Or glossed over.

The intricate design of the body

So wonderfully made, so elegant and precise

Stands at odds with its fragility and temporality

Like the perfectly aligned crystals of a snowflake

That melt instantly on my hand.

Dear Madam,

And I’ll never know some things about you

(Or him)

(Or her)

Because the rows of tables don’t have designer labels

Or desk plaques

Or balance statements.

Just ages and dates.

Dear Madam,

I don’t know anything about your house

Or whether you had a dog

Or how you drank your coffee.

And I see why some would ask,

Is this body all that remains of us, while everything else fades away?

Although I can’t help but believe,

This body is all that fades away, while everything else of us remains.

Meredith Citkowski is a second-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

A Strange Encounter

by Julia Johnson

“That was weird,” you said.

A sigh of relief escaped my body. I had been desperate to say something, but I didn’t have the courage. I was worried that you’d ask me to elaborate, and I was aware of the weight that came with my true thoughts on what we had just witnessed.

“What kind of mother calls her daughter stupid like that?” You asked.

Unfortunately, I knew a few. But, of course, we both understood it wasn’t just that.

It was the proximity of the two, the intertwinedness of them both. The way they entered the room, the daughter looking to the floor, her mother’s hand guiding her to the exam table, a grip on her shoulder. The urgency of the mother to answer a question, before apologizing and allowing the daughter to finish the response.

At first, I appreciated her self-awareness. She understood the need to humble herself when she wasn’t the patient. But after twenty minutes of repeating the same mistake, I became desensitized to the permutations of:

“Ah! I’m sorry I talk so much. I’m just worried about my daughter, but, of course, she should be the one to tell you what’s going on.”

I chastised myself for being suspicious. I knew nothing about them and was deluding myself into seeing things that weren’t there, enabling myself to assign meaning where it didn’t belong. I’ve always been prone to overanalyzing.

But, then, you gave me a look. A look that asked: Do you see it, too?

I wonder if you had been planning it all along, offering her that water bottle at the beginning of the appointment. Or maybe I was giving you too much credit. But, then again, she had joked about having the “bladder of a squirrel,” and perhaps the decades had made you clever in ways people wouldn’t expect.

It didn’t matter. Thirty minutes later, she asked to use the bathroom, and where you would normally have escorted her yourself, this time you called a nurse.

Time was precious, wasn’t it?

The door clicked behind her and you seized the opportunity.

“Did you do anything interesting over the summer?”

“What do you like to do in your free time?”

“What are your goals for the future?”

“How’s life at home?”

“Do you have friends? Surely, a twenty-six-year-old like you must be getting up to something!”

She laughed. A calm, inoffensive laugh.

I searched desperately for something there, something that was maybe being said without the use of actual words. I don’t know why. I’ve always been prone to overanalyzing.

“No, most days it’s just me and my mom.”

The mother came back. A notably fast trip, compared to most middle-aged women, I thought.

You carried on with the appointment, and before we knew it, they were gone, prescriptions refilled and referrals sent out.

When we went out in the hall, you were silent. I waited for you to say something. Eventually, you whispered.

“That was weird.”

Maybe it was to me, or maybe it was just to yourself. But the nurse overheard, and was curious why we were so hushed.

She had mentioned that the mother seemed anxious when they found that the bathroom was occupied. She had rushed to the next bathroom at the other end of the hall. Then again, maybe she just really had to pee. I’ve always been prone to overanalyzing.

But, at this comment, you had stopped typing.

Perhaps, I had a right to be worried.

The environment stood still. An eerie energy filled the space.

It was funny, and I think you thought so too.

Everyone knew those things happened somewhere, but it was always out there, wasn’t it?

Some place nebulous and ephemeral, halfway in our reality and halfway in our collective imaginations, a shared hallucination inspired by the cumulation of news articles, gossip videos, and court documents.

But those things didn’t happen here.

No.

Never here.

“I’m adding something to the note,” you said, “in case…”

You shook your head. You didn’t know how to finish the sentence.

We never saw them again.

Julia Johnson is a second-year medical student at NEOMED

A Differential Diagnosis

by John Kim

If my skin begins to harden,

eyes darken,

and all sensation from the world around me diminishes,

where is the lesion?

Consider a severe case of neuropathy

biological in nature

or

maybe I’m just tired

(psychological in nature?)

of reading about pain as if

it only existed

as letters on the screen,

a passing stranger

that I didn’t know I’d meet

once again, (to my surprise)

sitting in the exam room

with trepidation in her eyes,

that the doctor might see her

and read her once again

like letters on a screen

who will always be a stranger

Yes, I think I am tired

(it’s psychological in nature)

of holding back tears

that are fighting to breathe

the air on the other side

because it’s shameful

to let patients know

that I am human too

whom on my worst days

am just as fragile as

a candlestick of glass,

proud and slender,

that sits on the edge

of a high table

where medicine has seated me

and where I find myself unable

to locate where the lesion is

from this seat of glory

that came as if it were made for

those who deem themselves holy.

John Kim is a second-year medical student at NEOMED

Scoliosis Gallery

by Monica Wojciechowski

Artist’s Statement:

I have been an RN for 15 years and in my free time I like to draw. I decided to complete a collection about scoliosis, of which I am afflicted with and have gone through surgery, to help raise awareness of the condition.

Donald Duck - 8.5" by 11"; a portrait of the surgeon who completed my surgery, Dr. Richard Munk, who often talked in a Donald Duck voice to make his patients laugh; graphite on paper

The Serpentine Gallery - 11" by 17"; a study of a plastinated specimen from a donor with scoliosis; the specimen can be seen in the plastination museum at UTMC; graphite on paper

Real Women Have Curves - 17" by 11"; a study of a skeleton with scoliosis; black colored pencil on paper

The Masons - 17" by 11"; a study of scoliosis surgery; colored ballpoint pen on paper

Monica Wojciechowski (BA, RN) is an Assessment Coordinator at the UTMC Kobacker Center

Thingness

Image source: Unsplash

by Dr. Lloyd Jacobs

I have never felt my thingness more forcefully

than on that day my pacemaker battery was changed after

ten years dependence on its wires and connectors, set

opposite God’s three score ten, as beneath a Diocletian sword.

And the room where the change was carried out was a cavern

of x-ray and digital readout tubes; the walls and the ceiling

were festooned with murmuring cylinders and cubes

perched atop stalagmites or suspended from stalactites

I was a cog, a moving part in a buzzing beeping machine.

The dwellers in this cave were competent and automatic, they

crossed and re-crossed with unconcern the porous boundary

between kindness and condescension.

Dr. Lloyd Jacobs is President Emeritus of The University of Toledo. He has published 3 collections of poetry and was previously a professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan

Fracture Lines

by Shreyas Banerjee

I have found that feeling helpless is intrinsic to the experience of being a medical student. As a first-year, it’s always there, that sense of powerlessness. Every time you step into the hospital or face a patient, it sits with you. You watch the upperclassmen and the doctors—how they know what to do, how they know what to say—and you feel small. Useless.

In my first year, I often came face-to-face with my inability to help. My knowledge was thin, and the circumstances too heavy to overcome. Volunteering at a free clinic made it clearer. The people who came there were the ones who couldn’t afford to see a doctor. They came in with chronic conditions that couldn’t be fixed in one visit. The regulars, those who came for follow-ups and medication refills, they kept things in perspective. They were grateful. Their energy made it feel worthwhile.

But then there were the others. The ones that gnawed at you, the ones whose suffering stirred something deeper inside—something like rage. Not at the patient, no. At the situation. The way life had put them here.

Arriving at the clinic one day, I was somewhat excited. I was still somewhat new to the clinic but after several months of volunteering consistently, this would be the first week that I would be leading my team. Teams are usually composed of a clinical student, a pre-clinical student (that’s me), and a pharmacy student if available, all volunteers, with the clinical student leading the patient interview and examination. On this particular day, the clinical student I was paired with wanted to stand back and watch—it was their first time volunteering at the clinic—so I was assigned to take point. My excitement quickly turned sour as soon as I met my first patient of the night.

I saw a man in a wheelchair. That, of course, wasn’t unusual. But then I noticed how young he was, and how physically fit he seemed. No swollen joints or atrophied limbs—nothing like the chronic conditions I’d come to expect. Something terrible had happened. His brother accompanied him, and a woman introduced herself as a victim advocate from the county prosecutor’s office. She was there to ensure proper care. I was confused—free clinics weren’t usually visited by government-appointed advocates—but I started to take the patient’s history, just as my medical school had taught me.

The story began to unfold. The man had recently crossed the border from Colombia with his young daughter, hoping for work and stability. He stayed with his brother, who had arrived a year earlier, and six other men, all roofers. He joined them, but within a month, he got tangled in wires on a client’s roof and fell. Multiple injuries. A scaphoid fracture, a subdural hematoma, a trochlear nerve impingement, facial paralysis. But worst of all—a complete spinal cord transection from T4 down. I was in the middle of my neurology unit and had just learned what that meant. I tested sensation and vibration, reluctantly confirming the findings of the surgeons, whose notes the advocate handed me. She told me they were there for wound care instructions—he had a large open wound in his sacral region—and to coordinate follow-up care.

The man hadn’t been told how to manage his conditions or what his life would be like long-term. She also explained she was taking charge of his care to ensure the company he worked for would provide workers’ compensation. They hadn’t agreed to it yet. Many companies that hired migrant workers simply refused to pay medical costs, and some even dissolved and reformed under a new name to avoid liability. After all, they shouldn’t have hired an undocumented immigrant in the first place.

I stepped outside and took a breath, trying to clear my head. The weight of it all hit me. A man who had come here with hope, trying to build a better life for his daughter, now broken and helpless. He would never walk again, never care for himself, let alone his child. The anger rose in me then. How could this happen? Who had hired him and then left him like this? Did they think they could just use him and throw him away? And I knew they could. They probably would. The helplessness came back, stronger than before. It wasn’t just that I couldn’t help him. No one could. His life had been twisted by desperation, and now crushed by indifference. He was one of the many this country discards when they’re no longer of use.

What could I do? To fix a life is a hard thing for anyone, especially a first-year student. My training, in medicine or in life, taught me to see every problem as something to be solved. I thought if I learned enough, I could handle anything. But sometimes, even with all the knowledge in the world, there are things you can’t fix. I always knew this. But I didn’t understand it until then. And still, my helplessness was nothing next to his.

I stood there, the cold truth pressing down on my chest. The sun was setting outside, casting long shadows through the clinic's windows. I thought of the man, his broken body, his daughter waiting somewhere for a father who could no longer stand, no longer carry her on his shoulders. The advocate’s voice, steady and practiced, echoed in my mind, outlining all the ways the system had failed him.

I took another breath, long and slow, and stepped back inside. The man was waiting, his eyes calm but distant, the kind of calm that comes after too much pain. His brother stood next to him, hands in his pockets, as if holding in all the anger I had felt outside. The man glanced at me, a flicker of hope crossing his face, expecting me to do something, to say something. Maybe reassurance, maybe answers.

I could offer neither. I took his hand, not to heal but to hold. And we faced the silence together.

Shreyas Banerjee is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

The Art of Dying Well

Image source: Unsplash

by Luke Roberts

My first real encounter with death came in an ICU, not as a physician or even a medical student, but as a clinical researcher in the trauma department. Amid the rhythmic beeping of monitors and the soft whir of ventilators, I collected data points: Glasgow Coma Scales, injury severity scores, lengths of stay. But between the spreadsheet cells and statistical analyses, I witnessed something that numbers couldn't capture — the profound tension between our power to sustain life and our struggle to honor its natural end.

I remember one patient in particular, kept alive by an impressive array of machines after a catastrophic accident. The monitors showed life continuing, each heartbeat dutifully recorded, oxygen levels carefully maintained. Yet in the quiet moments between data collection, watching families wrestle with impossible decisions, I began to question what these numbers truly measured.

Now, as I begin my medical training, these experiences echo in unexpected ways. Our intensive care units stand as monuments to our defiance of mortality. The paradox of modern medicine is that our very success in extending life has transformed death from a natural passage into a medical failure. Each death in the hospital feels like a battle lost, a system malfunction we failed to correct. We mark it clinically: "Time of death, 3:42 AM." We document it efficiently: "Despite aggressive intervention..." We move on quickly: there are other patients to save.

But death has not always worn such a clinical face. Throughout human history, dying was understood not as a failure but as an art — one that required preparation, acceptance, and even grace. The Ancient Egyptians viewed death as a transition to another existence, with elaborate preparations ensuring this passage. They included The Book of the Dead in tombs and practiced mummification to preserve the body for the afterlife. Medieval Europeans followed the principles of ars moriendi ("the art of dying"), preparing spiritually and practically for a good death. Indigenous cultures worldwide developed rituals to honor and guide the dying, recognizing this passage as sacred rather than tragic. This wasn't a resignation to the inevitable; it was a deep understanding that the manner of our dying shapes the meaning of our living.

Today's medical students learn an arsenal of interventions: vasopressors, ventilators, ECMO, endless combinations of antibiotics and supportive therapies. We master the algorithms of ACLS and the protocols of sepsis management. Yet in our curriculum, there is little about the art of helping someone die well. The question facing modern medicine is not whether we can delay death — we have proven remarkably adept at that — but whether we should always do so. When does our technical ability to maintain life begin to interfere with our human capacity to die with dignity? The ventilator can keep lungs breathing, but at what cost to the person within?

This tension is fully apparent in our intensive care units, where the line between preserving life and prolonging death often blurs. Here, surrounded by the beeping monitors and whirring machines that mark modern medicine's triumph over mortality, we sometimes create a liminal space — neither truly living nor properly dying. What we need is a fundamental shift in how we think about death in medicine. Can we find a way to marry our incredible technological capabilities with the wisdom to know when not to use them?

This is not an argument for therapeutic nihilism or an abandonment of our duty to preserve life. Rather, it is a call for balance — for recognition that sometimes the most sophisticated medical decision is knowing when to step back. It is an acknowledgment that in our power to extend life, we must not lose our ability to support a good death. As medical students and future physicians, we inherit both the tremendous power of modern medicine and the profound responsibility to use it wisely. Perhaps our greatest challenge is not mastering the latest lifesaving techniques but learning to hold them in balance with the timeless human need to die with dignity and peace.

Luke Roberts is a second-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

The Ones We Leave Behind

Image source: Unsplash

by Merrick Harris

At the end of the day, shift, or call, when their work is done, the physician returns home, they relinquish their duties and reunite with their private life, a privilege forsaken while the demands placed by their profession consumed their attention. Yet their work is never actually done, if “done” meant their patients were cured of all maladies and released from affliction. As the physician rests, the environment they leave behind continues to be laden with suffering. They escaped, seemingly, temporarily from the immediate reminder of that environment, to which, as all humans are, they remain inextricably linked.

A senior medical student was assigned to learn from a man with pancreatic cancer, a man enduring extreme pain and often surrounded by loved ones. Each day, the student interacted with the man, his wife, and the occasional relative sentinel, communicating the medical team’s plan for the man’s treatment and recovery. The man was in agony, untouched by his manifold infused medications, and the student related to the man personally, staying a little longer than was usual to ease the questioning minds that surrounded him. Remarkably, the man steadily improved, and the family was increasingly grateful for each visit from the conscientious student, who provided a listening heart for their hopes and worries. Two weeks passed, and when the medical student’s final day of the rotation arrived, he said goodbye to the man, now undeniably improved as he talked and joked with the student, inviting him to visit outside of the hospital sometime. The medical student was graciously thanked for his diligence and empathy, and the family wished him luck in school. Thus, the student’s journey in medicine continued—like a planetary mass along its trajectory, leaving a dying star behind and entering a new orbit—and he began his next rotation at a new hospital the following day. The light emitted behind him, from the man and his experiences with him, had illuminated the student’s path ahead, now certain in the type of medicine he would pursue. But, as tends to happen at great distances, the student did not realize that the light source behind him, that same day, had already gone out.

The responsibility to care for patients is temporary, and the time available to spend with them quickly passes; there are perhaps few professions more familiar with the brevity of life than those in healthcare. The medical student enters this reality during their training, with the respite that distances them from it diminishing greatly in residency—so designed to help the physician better understand patient suffering by taking part in it. Yet despite immense effort, at the end of their career, the physician leaves behind the same fact of sickness as when they embarked to cure it. The next generation of providers similarly assumes their Sisyphean mantle and comes to the recognition that, in the end, medicine only painstakingly prolongs the inevitable, when dust returns to dust. But, regardless of the difficulty of its path, there is still profound meaning in medicine, and, for the sake of the ones we leave behind, we must pursue it.

Patients are more than the sum of their biologic and chemical processes; they possess a constellation of beliefs, motivations, and experiences that are inseparable from their health and well-being. For medicine to have a lasting impact, its delivery must be combined with that which is unopposed by the physical condition before it—it must be accompanied by love. The relationship that blooms between a patient and provider transcends biologic treatments, overcomes physical limitations, and reaches where medicine alone cannot—to the human spirit within. Compassion and empathy are not mere supplements to effective healthcare, but they are integral to it. Without them added to the physical benefit medicine may provide, an infinitesimal benefit it remains.

We are all dying stars; how long we are perceived to emit light depends on how far it reaches, and if anyone cares to look.

Merrick Harris is a fourth-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

Fragments from an Outbreak

by Chinenye Ezema

Painted 12/2020 on a 16x20 canvas

Artist’s Statement:

I made this painting to capture the mix of fear, uncertainty, hope, and loss, that was experienced during the pandemic. During the "lockdown,” emotions varied greatly from grief and loss of a loved one to the boredom of a teenager stuck at home. The days stretched endlessly, whereby some people enjoyed an unrequested time off, while others searched frantically for things to do, due to the sudden lack of a routine.

Dr. Chinenye Ezema is a licensed pharmacist

A Farmer’s Legacy

Image source: Unsplash

by Namrata Kantamneni

They say that when a farmer steps into your clinic of his own volition,

It is no ordinary visit—

It is an emergency.

For these are the most resilient of men in society,

Toiling long and hard hours in the fields,

Stoically dismissing away pain and fatigue.

When I see such a patient,

I am reminded of my grandfather.

A man who farmed the land his entire life,

Who had the utmost respect for his profession,

Who treated the Earth with the dignity she deserves,

Who cared deeply for each individual in the village.

A man I’ve never met,

But whose legacy courses through my veins,

In my own stubborn psyche.

He died suddenly in his thirties,

Leaving behind his five older sisters,

As well as a young wife and teenage son.

His passing was sudden—

A brain hemorrhage,

Triggered most likely by underlying hypertension.

The sort of terrible headache you read about in textbooks,

A headache so bad,

That you vomit from the pain.

But for a farmer,

It is simply another headache.

Nothing a little painkiller can’t fix.

When I see such a patient,

I see my grandfather.

Transcending ethnicity and culture,

I see that same person,

With the same work ethic,

With the same stubbornness and dedication and willpower,

With the same tender love for everyone in his life,

With the same respect for Mother Earth.

When I see such a patient,

I’m not straddling between India and America,

Pondering differences between the two,

Confused by a false dichotomy.

Instead, I see the divine spirit present in my fellow human,

Oneness transcending culture into universality,

Binding all of humanity together.

A reminder,

That we are all the same in God’s eyes.

Namrata Kantamneni is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

Giving My First Gift of Life

Image source: Unsplash

by Kolby Quillin

During medical school interviews, many students, including myself, would have liked to answer the question “Why do you want to become a doctor?” with the cliché “I like science and want to help people.” However, as pre-clinical medical students, our job is to learn the science to earn the privilege to help people. Many students find time in their busy schedules to work with the community, helping people just as they had wanted to.

In the scramble of first-year medical students finding their place into organizations, I fell short. At my own fault, I quickly became out of touch with most service opportunities. Seeing all my fellow classmates doing incredible things for the community made me feel like a disappointment to my past self. I came to medical school to help people, but just spent every day flipping through flash cards.

This story really begins my sophomore year of college. During a club meeting, a fellow student came to present on behalf of an organization called “Gift of Life.” They explained that this organization was creating a stem cell donor registry for people suffering from blood diseases. We then had the opportunity to join the registry ourselves. Alongside my friends, I swabbed my cheeks and filled out my contact information. Then, quite frankly, I forgot about it for five years.

After finishing college and completing my first year of medical school, I found myself back in my parents’ house for summer break. At this time, I was relieved to be able to relax but still felt I had missed out on something my M1 year.

One day while driving home, I got a call from a Florida area code. Thinking it was a spam call, I didn’t pick up. Again, they called, and again, I didn’t pick up. The next day, I got the same call, but this time I decided to give the “scammers” a piece of my mind. However, I was met with an actual human on the other side. A lady told me that she was with an organization called Gift of Life, and she was reaching out because my swab sample was a match for a 67-year-old man battling Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. She explained that I may have an opportunity to save this man’s life through a stem cell donation and that I should take some time to talk to my family about the next steps.

My mind immediately began to race. I would be remiss to exclude a serious phobia of mine. Ever since I was a child, I have been terrified of needles. On cue, seconds after most vaccinations, I feel lightheaded and pass out. As someone going into a career surrounded by needles, this may sound comical. But after discovering that I would have to receive over a dozen injections, my brain told me to run. I couldn’t help it, but I wanted nothing to do with it.

For most of the day, I sat with the conclusion that I would not proceed with the donation. I felt I was not the right person for this. I told my family about the situation, and they immediately acknowledged my phobia. However, they encouraged me to reconsider, expressing the significance of the situation. Trusting their judgment, I began to think of my time learning about AML in class. I thought about the symptoms this man was experiencing, and I remembered my whole reason to pursue medicine in the first place: to help others. While I may be afraid of some needle pokes, it didn’t compare to what this person was going through. It became clear that the best thing to do was to proceed with the donation.

I called Gift of Life back, and tests were set up to determine my human leukocyte antigen typing and reveal any pathogens I may be carrying. Soon after, I went to get my blood drawn, and I still felt a bit nervous. Per my usual routine, I told the nurse about my habit of passing out, and she made sure I lay down as we did the draw. In that office were 11 empty vials staring at me, but the idea that this could save a life overtook my thoughts. As the needle went in, I was frightful, but it was over before I knew it. For the first time in ages, I proudly made it out of a blood draw without passing out.

Later that week, I got another call from a Florida area code. This time, I couldn’t wait to answer. Over the phone, I was told that my match was confirmed and that they would like to proceed with the next steps. The reality of the situation kicked in and I was flooded with anticipation for what was to come. We scheduled a physical exam to ensure my body was fit for the procedure and settled on a date for the actual donation. After confirming with UTCOM, who graciously allowed me to take a week for this opportunity, Gift of Life booked a flight and hotel for me and a guest. They cover all costs associated with the procedure, so it is a cost-neutral experience for donors.

I soon found myself on the beaches of Florida with my girlfriend. Everything was coming together, and it was almost time for the donation. Gift of Life set up a home nurse to come to the hotel every day for me to receive Filgrastim injections, which is a G-CSF used to promote stem cells from bone marrow to migrate to the peripheral blood circulation. While I can’t say I looked forward to receiving three injections every day, the nurse was incredibly professional and eased any anxiety I had. Every day of injections conditioned me to not fear them, and they became easier and easier for me.

Between injections, I spent my time watching lectures on the beach, doing some fishing, and got to celebrate my 25th birthday over dinner. Gift of Life ensured my comfort through the whole experience and provided us with all the snacks we could ever want. Other than a slight sternal ache due to my stem cells releasing from the marrow, I had no side effects from the Filgrastim.

Before I knew it, donation day came. A car came to pick up my girlfriend and I from the hotel. The driver was almost as excited as I was. Upon arrival at the donation center, we were met with a smile on everyone’s face. It was clear that every employee there loved being able to assist in these special moments. They made the morning feel like a celebration, as we were all working together to save someone’s life.

I received my final Filgrastim injections, which at that point had become as simple as brushing my teeth, and was hooked up to the apheresis machine. This machine took blood from my left arm, spun out the stem cells, and returned it back into my right arm in a matter of seconds. The nurse was masterful at his job, constantly checking in on me to ensure I never was cold or hungry.

After 4 hours, my time on the machine came to an end. In a bag sitting next to me were my stem cells. That bag was going to be used for something much larger than myself. It represented both a life saved and my conquered fears. We took pictures with the staff and my cells were sent off on a plane to the recipient’s treatment center to be transplanted that day.

As I write this, I am awaiting 6th-month updates on my stem cell recipient. I don’t know the man’s name or where he is from, but it is heartening to know that a little bit of me is somewhere out there, aiding in his recovery. This experience gave me the sense of purpose that I had longed for during that first year of school. As I transition into a career of medicine, I hope to help many more people heal from disease. I will always remember this as the first time I felt I achieved this dream.

If you ever come across a Gift of Life drive, I recommend you consider swabbing. While some patients suffering from blood diseases find donor matches through their family members, 70% must utilize registries like Gift of Life for their potentially lifesaving treatment [1]. Gift of Life is an incredibly professional organization and led me through every step of the process. I truly can’t praise them enough for how they accommodated all my needs. This has been the most fulfilling moment of my life, and I hope that countless others can experience that moment too.

Bibliography

Gift of Life Marrow Registry. 5 Steps to Save a Life. Gift of Life. Accessed February 3rd, 2025. https://www.giftoflife.org/donors/donationprocess1

Kolby Quillin is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

An Exercise Pill for Couch Potatoes

by Sachin Aryal

On a recent flight returning from the American Physiology Summit, I was seated next to a gentleman who was unfortunately not comfortable in his economy class seat due to his large size. We began chatting, and he told me that his doctor had diagnosed him with metabolic syndrome and that he hated exercising, although he was told that exercise would help him. I asked him if he would like to take a pill as a substitute for exercise. He was all ears.

Like this gentleman, there are millions of people around the world who are unable to exercise due to many reasons, such as ill health and physical limitations. Such individuals are more prone to metabolic syndrome, a condition which often presents high blood pressure, high body weight, high blood sugar, high bad fat in the blood, and a very low level of a biochemical in our blood called β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB). BHB is a ketone body that our bodies generate at a high level during exercise. This is to meet the increasing need for energy.

Our body normally uses glucose as a source of energy. But during intense exercise, when glucose is used up, we tap into using stored fats in our bodies to meet the demand in energy. When fats are broken down, BHB is formed. Intriguingly, we and others have found raising BHB in our blood has profound beneficial effects on blood pressure and body weight. Luckily, we found an FDA-approved chemical called 1,3-butanediol (BD), which, when consumed, converts into BHB. Therefore, I asked whether nutritional supplementation with BD could be used as a simple substitute for exercise. The sheer thought of this being a successful study brought a chill to my spine, thinking about my research yielding a solution to help folks like my plane friend.

For my experiment, I used rats, which are known as the low-capacity runner (LCR) rats. Unlike their healthy counterparts, which love to run on a treadmill, these rats are “couch potatoes” which do not care to run when introduced to a treadmill. Earlier work has shown that the LCR rats are prone to metabolic syndrome. So, they were perfect as models to test my hypothesis that feeding BD would lower their metabolic syndrome. I used two groups of LCR rats. Water given to only one of the groups was spiked with BD. The study went on for 9 weeks, during which I monitored their blood pressure and body weight periodically. Blood pressure of rats was monitored continually via a surgically implanted radiotelemetry device into their major blood vessel, the aorta. At the end of the study, I humanely euthanized the rats through approved protocols and collected their organs for further study.

My expectation was that the rats administered with BD would have lower blood pressure and body weight. During the early two weeks of this experiment, I was rather disappointed because both the groups of rats with or without BD treatment had similar blood pressure and body weights. But the eureka moment was in week 9 into my study when I observed that the rats administered with BD had significantly lower blood pressure, blood sugar, and body weight compared to the rats that were not given BD. My happiness knew no bounds! I knew at that moment that I had discovered something that would hopefully one day help folks like my plane friend.

But an important question remained. How? How did BD work? For the first pass, we checked whether the animals receiving BD did elevate BHB. Yes, they did, and that was good. But how does BHB operate to lower blood pressure and body weight? This is currently my ongoing research work. So far, we are convinced that one of the ways by which BHB operates is deep within the cells of our bodies, inside the cell nuclei, where it binds to specific proteins that serve as spools for our DNA. These proteins are called histones, and the process of BHB binding to histones is called histone β-hydroxybutyrylation. What happens next is fascinating. I found that by binding to histones, BHB causes these “spools” to specifically open at certain spots, whereby the “thread” or long chain of DNA opens, and the genes located within these open regions of DNA are then decoded to make proteins which break down fat. This explains why the rats given BD lowered their body weight. But how does this process lower blood pressure, too? This is the question that I am currently working on towards my PhD thesis.

Our bodies are amazing machines, the parts of which are called “anatomy,” and the way the parts work in complex ways is called “physiology.” I am proud to call myself a researcher in this field of medicine, which connects the dots and lets us understand the secrets of our bodies from form to function. From my experience thus far, the thrills and spills of research swinging from disappointments to excitements as the answers to my research questions unfold are ones that I would never give up. The bonus is the thought that one day my work could help improve the quality of life of some people like my plane friend.

Back to my conversation with my co-passenger on the plane ride, he was fascinated with my research and asked if he could get some BD. Well, that was beyond my capacity, because I am only a researcher working with pre-clinical animal models. There are strict regulations whereby further experiments must be conducted in human clinical trials before federal approvals can be obtained for BD as a supplement to correct metabolic syndrome. When that day dawns, I know that I will experience priceless joy for having contributed my small might to make it a reality.

Accompanying graphic art as a component of the author’s PhD project

Sachin Aryal is a current PhD candidate

Look, Listen, Palpate

Image source: Unsplash

by Gabriel Bonassi, Shreya Bhoopathi, Sofia Boiajian, Tarak Davuluri, Andrew Edgington

The Toledo Botanical Garden is an important landmark in the city, known for its native wildlife and rich historical background. Our team explored the Garden using the "look, listen, and palpate" method. This involved appreciating the park's visual aesthetics, listening to its ambient sounds, and palpating its textures to learn more about what it has to offer. Through this method, we discovered the Garden enhances Toledo's landscape, preserves its cultural heritage, and serves a communal purpose.

Let's take a trip back in time to 1963, a prosperous year that reimagined culture within the "Glass City" of Toledo. Amidst the molten glass that forged skyrises and aspirations, a quieter legacy began to unfold. During his passing, prominent realtor and businessman George P. Crosby, in an extraordinary act of generosity, donated his 20-acre horse farm to the city. Today, that generous gift has grown into the 60-acre Toledo Botanical Garden, a space that represents a devoted community's commitment to preserving green spaces and promoting inclusivity.

Park supervisor Steve S. Ford notes that the Garden has grown to be much more than a serene escape. Through his involvement in building and designing the new inclusivity Garden, Mr. Ford mentioned how the new space was designed to accommodate everyone. "We wanted to engage all the senses to invoke memories," Mr. Ford explained, gesturing to a circular pathway of bricks that each produce a unique sound when rubbed with shoes, which provide essential auditory cues to visually impaired visitors navigating the space. "Now stand still and close your eyes," Mr. Ford said enthusiastically. Within a couple of seconds, the sounds of nature were amplified by our tympanic membranes. Following the rapid conversion of sound waves to electrochemical signals, our vestibulocochlear nerves promptly delivered this information to our somatosensory cortexes. In return, we were rewarded with the pleasant harmony of wind, birds, and rustling trees. "The area is also wheelchair accessible and up-to-code," says Mr. Ford, who was proud to create a garden that invites everyone to share in its beauty. The Toledo Botanical Garden is an excellent example of how Toledoans take the extra time to increase the accessibility of public parks.

As we continued to explore, we came across volunteer John, who was hands-deep in a bucket of soil, tending to the nationally recognized, award-winning lily collection. "This here is Becky Lynn," he said with a chuckle, introducing one of the lilies as if she were an old friend. The lilies we saw, carefully tended and named, stood as quiet witnesses to the decades of community care, reminding us that beauty in the Garden is not merely seen but nurtured over time. While telling us about the history of the Gardens, it was divulged that a possible mythical moon tree, sprouted by a seed carried by the real Apollo 14 mission, might be present in the park. However, that is just one of many fascinating stories and myths told by volunteer John. Through our conversation, he also brought up how the Botanical Garden hosts the annual Crosby Festival of Arts, which honors the land donation of Mr. Crosby in its name. This lively event hosts around 10,000 people a year, complete with food, drinks, and live music. With continued festivals since 1965, it is officially Ohio's oldest outdoor juried art festival. In contrast to the liveliness of these festivals, our impression of Toledo Botanical Garden noted a quiet, calming atmosphere that allows its visitors to genuinely enjoy and embrace the natural beauty they find themselves in.

Beautiful lily collections aside, Toledo's Botanical Garden offers unique visual experiences of nature infused with art and history. A promenade lined with grand silver linden trees welcomes visitors at the entrance. Along the path, large decorative urns with relief carvings depicting early village life can be found, cracked and chipped along the surface with a rustic finish. At the Garden's center lies Crosby Lake, featuring distinctive yellow boat-like sculptures that are moved by the wind. In the picturesque, tree-lined Grand Allee, we noticed a statue of Flora, the Roman Goddess of flowers, extending flowers in her hand. As we looked around, Peter Navarre's cabin came into view. Born in Detroit in 1785, Peter was known for having served General William Henry Harrison as an Indian scout in the War of 1812 and for his skill in woodcraft. We noticed a diverse vegetable garden sitting proudly right outside his cabin, giving us a glimpse of the lifestyle of early settlers and their traditional practice of agriculture. Next to each plant, detailed plaques share stories of food and cultural exchanges, offering glimpses into the rich history behind Toledo's development.

In every corner, the Toledo Botanical Garden shows the city’s commitment to a community space that preserves natural beauty. The diverse assortment of native flowers and vegetables in the city provides a glimpse into the life of Toledo natives prior to city life. We see the progression of trade between different cities through the addition of plants in the Garden. The auditory component was noted in moments of quiet, broken by the soft rustling of branches and people talking with their loved ones. These quiet moments allow Toledo residents to reconnect with nature and the people around them. Palpating the various plants and artifacts in the Botanical Garden reminded us of the people who lived in Toledo before us. All these experiences led us to understand the history of Toledo and the progression of our city since it was settled. The variety of plants that are not native yet are finding a way to thrive parallels the warm greeting that Toledo extends to everyone who enters the city.

Gabriel Bonassi, Shreya Bhoopathi, Sofia Boiajian, Tarak Davuluri, and Andrew Edgington are second-year medical students at the UTCOMLS, where they are team members in a team-based learning (TBL) group