What We Stay Alive For

Image source: Unsplash

by John Kim

“…And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

-Dead Poet’s Society

Reading is one way in which I occasionally allow myself to be distracted. One day last Fall, I had chosen to read The Good Doctor, a short story assigned to us in preparation for a discussion on the value of narrative within our medical curriculum. I was a few hours into a rather frustrating study session on histology and the story of Mrs. Buckholdt, a 44-year-old woman with a psychiatric disorder, and her visiting physician was just what I needed to forget the miasma of purple and pink swirls, spots, and streaks that were taking over my mind. Two pages in, I could almost smell the “stale candy and the chemical salts of cheese-flavored snacks”1 as I, alongside Mrs. Buckholdt’s visiting psychiatrist, entered her house. We called out to her together, as if greeting a patient whose room we had just entered. Both of us had traveled a long way to see her; him from a driving distance of two and a half hours, and I from my own world on the other side of the page. However, unlike the psychiatrist who had gone through years of training to think like a doctor, I had just begun my medical education and was less inclined to do so.

The next week, I shared with my peers in my discussion group about the trip that I took to Mrs. Buckholdt’s place. I told them how her gaze had lingered on a print of a painting hanging behind us (Brueghel, I think) and how I had wished that the psychiatrist had taken up the subtle invitation to converse about it. I lamented how it was a lost opportunity to connect with Mrs. Buckholdt and wondered whether it was at that moment that she had decided to no longer be our patient. The definition of a “good doctor”, something which I had been pondering about long before the start of my first year, proved elusive still. I had hoped that the number of hours invested into my studies would, by bestowing me more knowledge to act upon, allow me to draw me closer to that definition. However, any reference or usage of medical knowledge seemed to hinder more than help in the situation that I had found myself in. Oddly enough, the “good doctor” that I envisioned turned out to be someone who could think, appear, and feel less like a physician.

As I wrestled to resolve this paradox, I was reminded of many small moments during my first year that had been memorable, simply because of how they had allowed me to forget that I was studying medicine. I found myself conversing with a stranger at a climbing gym about EDM festivals that took place in forests, tearing up after having finished a tragic TV show about love in a futuristic city, and watching proudly as my sister got married to an old friend of mine. It was moments like these, or the feelings that they came with, which taught me something that my medical curriculum had not; the joy that comes with living.

Last year, I had the chance to read Being Mortal by Dr. Atul Gawande (2015), a practicing surgeon who has authored other well-acclaimed books on healthcare such as The Checklist Manifesto. In his book, Dr. Gawande presents to us the stories of his patients, including his own father, to introduce a compelling question about what it means to really live. Medicine has traditionally been concerned with preserving and extending life, which has allowed us to live longer and become more resilient to sickness. While this is a notable achievement, Dr. Gawande argues that life is pursued based on the reasons we wish to live it for, not necessarily the length to which we can extend it. Medicine, with all its miraculous ways of governing biological processes, can enable us to pursue well-being on our own terms.2 When given the opportunity to live, we wish to do so with autonomy, fulfillment, companionship, and a lasting degree of childlike curiosity as we are left to freely interact with the world around us. To live is to be both present in our moments and present with whomever may be with us during those moments. It is a deliberate effort to regain control of our autopiloting selves and allow ourselves the luxury of connection, whether it be human, natural, or spiritual. There is no better way to see a person than to see how they seek out these connections, and how they are weaved into a magnificent amalgamation of comedy and tragedy that represent who they are. This perspective is what is emphasized in the medical humanities curriculum; to emphasize the role of our various identities, experiences, and the connections made between them as tools for cultivating empathy and patient-centered care, ensuring that future physicians do not lose sight of the people behind the illnesses they treat.

Reading stories such as The Good Doctor helps me to regain control, albeit for a brief moment. As a medical student, there is always more to study and never enough time to do so, so I find myself constantly chasing after that elusive feeling of accomplishment, hidden at the end of several lectures and hundreds of Anki cards. It doesn’t occur to me that somedays, it is enough to simply be a son, a brother, a neighbor, and a friend, until I find myself in Mrs. Buckholdt’s living room next to a psychiatrist who can’t see past his desire to write her a prescription. Unlike the syntax and jargon used by this psychiatrist to assert his own control and authority, the language used by the authors of such stories is familiar, relatable, and reminiscent of my days before the chaotic demands of medical school, a time when it felt more natural to be humane and caring. The past two decades have shown growing support among medical educators for the value and necessity of humanities training in medical education, which approves the use of such familiar language.3 These include the “old words” described by Dr. Kumagai*, an endocrinologist and a long-time health humanities scholar, as those of which we have heard before but may have forgotten their relevance to ourselves, words such as “wonder” and “mystery”. As a champion for the health humanities, Dr. Kumagai has advocated for the need to teach medical students how to supplement their vocabulary with words that can expand their spectrum of human expression and understanding.4 The trajectory of my medical education emphasizes the importance of basic sciences where these “old words” tend to get buried under more objective language describing data and processes. I find myself struggling to apologize, to empathize, and to encourage, all of which rely on my mastery of the “old words”. Without them, my conversations turn into stale formulas and I may, not unlike Mrs. Buckholdt’s psychiatrist, also find myself being overtaken by the numbness that comes with chronic overexposure to pain.

Most of us can probably remember a time when neither school nor spirit kept us from giving ourselves over to the various distractions of life. I remember sleepovers with b-horror movies, 2-hour long waits for amusement park rides, and beach picnics that served sand-laced sandwiches. Once while I was still working on medical school applications, I heard that some of my favorite local House music DJs were invited to play at an event in my city. I drove there alone on the day of the event, dressed casually and carrying nothing else but a heart full of anticipation. I danced for hours that night in a dark bar with a low ceiling amongst strangers and heard nothing else but the constant stream of music coming from the speakers. Distractions such as these transport me out of the molecular level of thinking and place me amidst the human experience of what it means to live, to love, to become sick, and to become well. It speaks to me the importance of “[the] awareness of bearing witness to and participating meaningfully in those events that make us human”4 which is ultimately what is highlighted in our medical humanities curriculum. As aspiring clinicians who will help sustain and improve the lives of others, it is important that we connect with the experiences of our patients that enrich and elevate their lives. It is also equally important that we find ways to enrich ours as well. The reasons for which we stay alive, as opposed to the act of survival itself, may be crucial in defining our personal and professional success as student-physicians. Thankfully, those reasons may not be too far from us, perhaps waiting to be uncovered in the next distraction that comes across our way.

1. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. London: Picador Publishing; 2015. 304 p.

2. Kumagai AK. Beyond “Dr. Feel-Good”: A Role for the Humanities in Medical Education. Academic Medicine. 2017 Dec; 92(12):1659-1660.

John Kim is a second-year medical student at NEOMED

The Plan

Image source: Unsplash

by Namrata Kantamneni

Wake up at 5:30 am. 30 minutes of yoga. 30 minutes of running. Shower. Say a quick prayer with the prayer beads. Breakfast is millets and almonds. Pack my backpack and lunchbox. Head to class by 7:45 am. Class runs till noon. Lunch consists of brown rice with curry made of lentils and vegetables, and plain yogurt rounds out the meal. Then I study through the evening: 1 hour of Anki flashcards, 2 hours of UWorld practice questions, 2 hours reviewing concepts, 1 hour answering emails and other random tasks. Sleep by 10 pm. Rinse and repeat.

I like routine. I like pushing myself. It’s why I fell in love with long-distance running and chose to run cross-country and track in high school—the intoxicatingly alluring runner’s high of pushing past the moment when mind screams surrender and body begs you to stop and give up. The joy of racing in a competition with yourself. The feeling of satisfaction when you keep going, mile after mile, no matter what.

Indeed, isn’t it true that nothing worth having in this life comes easy? That effort makes the end result all the more satisfying?

It makes sense, then, that I find comfort in the plan I set for myself when I was a teen, a plan to be the best physician-scientist I could be. A 50-year life path I wrote out when I was 15. This plan is why I don’t like distractions, nor any changes in the trajectory I set for myself. Because I believe that success is 99% hard work and 1% luck. So if I stick with the plan, with no deviations, I will be the best I can be.

Right?

And yet, a little voice tells me that there is something more. A world outside of this vision of the future I have for myself. I see this world in my artwork from 8th-grade drawing class, in middle school notebooks filled with poetry, and in medals on my bookshelf from singing contests. That world was bright and colorful, filled with fantastical dreams.

I don’t know what happened to that fiery girl. The one who would get into debates and arguments and fight for what she believed in, even if that meant voicing an unpopular opinion in the midst of her peers. The girl who wore braids to school every day, even when the other kids would pull on them and make fun of them. That girl never touched a textbook, instead preferring to help her mother in the garden and get her hands dirty in the soil.

That little girl didn’t know anything about the MCAT, USMLE licensing exams, networking events, or residency. She didn’t do extracurriculars just to “build her CV,” and she certainly didn’t care about climbing the ladder of ambition.

When do we lose that part of ourselves?

It would be easy to point to a singular moment in time, a point when the harsh reality of the world set in and we had to “grow up.”

But in my opinion, that is far too simplistic an answer.

Instead, it happens slowly.

It insidiously creeps up, a sort of “death by a thousand cuts.” Slowly, the fantastically colourful and passionate world of our childhood loses its color. We stop doodling in our sketchbooks on a random Wednesday, stop playing with the rocks in the garden on a random Sunday, and stop observing the way the earthworm moves in the soil on a random Monday.

Instead, we build castles in the sky. These goals and plans start in high school, with AP courses and SAT prep, class rankings, and the dream college acceptance. They shapeshift in college, changing to MCAT scores and organic chemistry labs, and the hope of getting into the dream med school. Then in med school, the goalpost changes again, instead, this time filled with research projects and volunteering hours and Step scores and matching into the dream residency.

And over time, as the goalposts changed, so did I. Slowly, but surely.

And I don’t know the solution for this.

But today, it is raining. And though not a solution, the rain gently cools and tempers the fire within.

The rain begins softly, droplets kissing the blades of grass, a gentle rhythm filling the quiet of the morning. The sky fades into a hazy gray, a muted but beautiful canvas. Some might crave the warmth of a fireplace on a day like this, but instead I find myself longing for the rainy drizzle, for the cool dew on my brow, for the breeze brushing my cheeks. A reminder that the world is alive, God’s pulse surging through every atom of my existence.

So I don my running shoes and step outside.

As I run, my thoughts run too, tumbling like stones in a stream: the coagulation cascade—do I recall its intrinsic and extrinsic pathways? The steps of the urea cycle? Cholesterol synthesis, cranial nerves, forearm muscles, their innervations—the endless notes of a mind tasked with ever-looming exams.

I wrestle these thoughts to soothe the stormy, turbulent waters of my psyche. To find the calm that yogis have perfected over millennia.

But calm evades me.

Instead, my unquiet mind turns to the past, the present, the future.

Thoughts rush in, like the muddy rain percolating through my socks: Am I doing well enough on practice questions? Should I take on another research project? More evenings volunteering at the free clinic? How can I do well on my current rotation? What else do I need to do to match my dream residency? What if I change my specialty? What should be my backup plan?

The thoughts flit, restless birds on a windowsill. They grow louder, building castles in the sky— residency, career, family, endless decades of to-do lists, spinning faster and faster, much like my legs in the final mile, sprinting as the rain turns into a storm.

Faster, I sprint. The burn spreads through my mud-caked calves. Breathless, my lungs heave. And in that searing pain, the thoughts dissolve.

For one fleeting moment of respite, my mind is blank— free.

Namrata Kantamneni is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

Flowers in Bloom

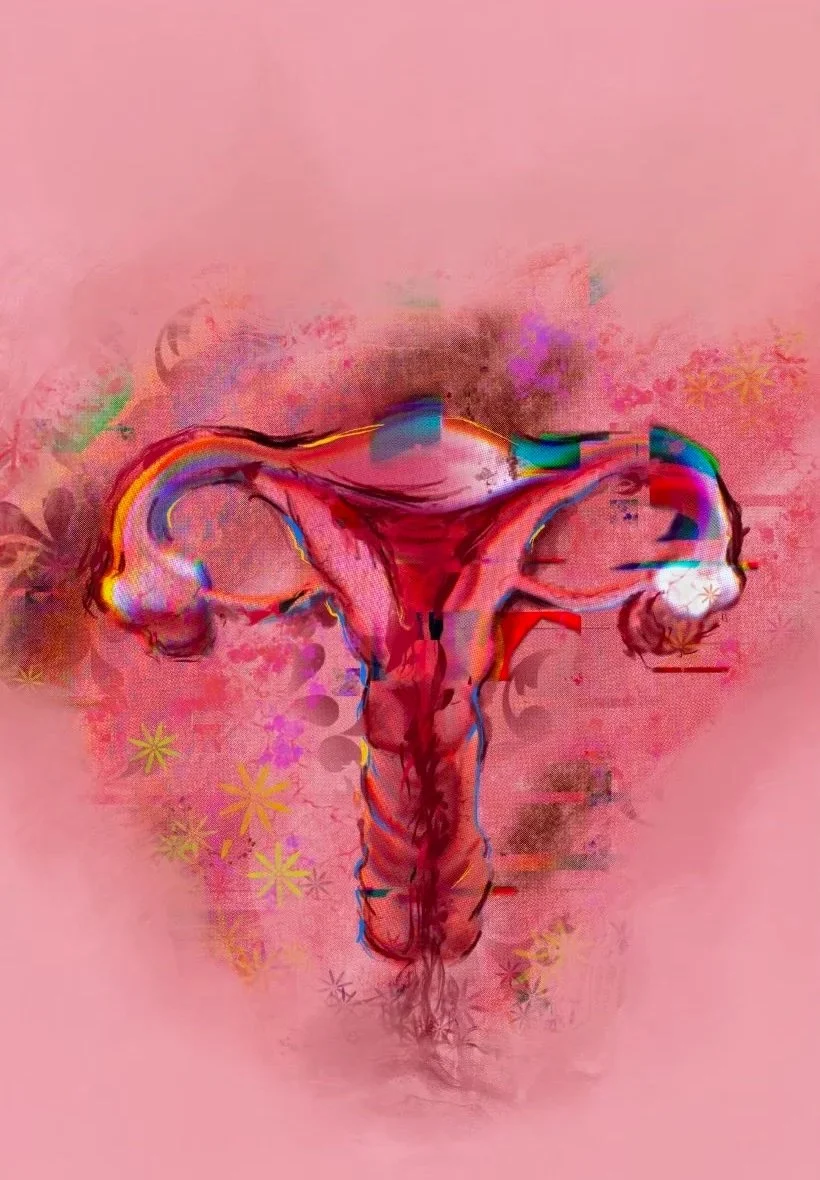

by Shruthi Varier

Digital Art

Artist’s Statement:

Art has historically been a point of self-expression, representation, and resistance against the struggles faced throughout one's life. Reproductive rights and patient autonomy are constantly under scrutiny, especially within today's political climate.

Surrounded by blooming florals and intermingled with psychedelic, hippie-inspired elements, this piece depicts an anatomical uterus. The flowers sewn into the endometrium work as a nod to fertility, growth, and resilience. If observing carefully, the viewer can note that the movement of the floral work follows with the shedding of the endometrial lining.

Incorporating counter-cultural aesthetics, free form waves, and deep tones of reds and pinks with splashes of the comprehensive color wheel, this piece is meant to challenge the viewer to expand their perspective on reproductive rights, moving from the rigid hierarchical control that is often placed upon those who carry a uterus towards emphasizing self-autonomy and creation.

Shruthi Varier is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

The Choice: One woman’s experience

by Tricia Aho

I’m pregnant again! My ten-month-old daughter will have a sibling! If only I can carry this one to term…

Ms. X has lost several pregnancies, often feeling as though it was her fault, and she was failing at something. That something she was doing was causing her to lose her beloved pregnancies. But the last pregnancy resulted in the birth of a beautiful baby girl. Imagine her guarded excitement knowing that she was growing another beautiful child.

As she progressed through the pregnancy, she followed closely with her OB, never missing an appointment due to her high-risk status. After a prenatal ultrasound at 12 weeks, she was brought back into a small consultation room. A room she had been in before, when she was told she miscarried. She was alone, as it was a routine appointment with a healthy pregnancy, and her husband had to work. She called her husband in a panic, bracing herself for the devastation she knew was coming. Sobbing as she hung up the phone, the doctor walked in to deliver the news. But this time was a little different: her baby was still alive, but appeared to have a genetic condition that would result in death soon after delivery, if not during the remainder of the pregnancy. Ms. X was faced with a choice: to follow her OB’s advice to terminate her pregnancy that would likely still result in a loss, to undergo amniocentesis, which would give her more definitive answers but would increase the risk of miscarriage, or to continue the pregnancy with the hope of one day meeting her child, even if only for a short time.

Ms. X had suffered enough loss. She didn’t know how much more she could take. But she knew that she did not want to give up on her baby. She wanted her daughter to have a sibling. And she didn’t want to do anything that would increase her already-high risk of miscarriage. After much distressing consideration and conversations with a friend who was a geneticist, Ms. X, with the support of her husband, ultimately decided to continue the pregnancy. Approximately six months later, another baby girl was born, who continued to grow and develop normally, with no signs of the genetic condition that forced Ms. X to make the choice.

It is often implied that being pro-choice equates to being pro-abortion. However, the story above describes Ms. X’s experience… she personally describes her beliefs as being pro-choice but emphasizes that the choice to have an abortion was not the right choice for her.

As clinicians and future clinicians, it is our duty to our patients to provide them with as much information as we can to help them make an informed choice regarding their own healthcare. While we may have personal beliefs that oppose those of our patients, it is imperative that we set our beliefs aside in order to honor the wishes and needs of our patients. Especially when we cannot be certain the outcome will be what we expect.

Ms. X is not a patient I encountered. She is my mother. And I am the child she would have lost had she made a different choice – one which she could not have made without her doctor communicating all available options and risks, and respecting her wishes even when they differed from her OB’s recommendation.

[Story shared with my mother’s permission]

Tricia Aho is a fourth-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

False Dichotomy

Image source: Unsplash

by Namrata Kantamneni

Career or family?

On the subject of marriage, we often declare our need to prioritize our professions.

But is that truly the whole story, that we must choose only one?

I reflected on this question as I sat in the car next to my mother,

Confused after receiving my acceptance to medical school.

Hot tears softly slipped down my cheeks as I wondered whether I had made the right choice,

Leaving behind the security of a stable job, uncertain of what lay ahead.

I witnessed the toll that the medical profession exacts,

Devouring those who enter with hopeful expectations born from their gentle souls,

Transforming once-compassionate doctors into frazzled shells of their former selves,

Stripped of energy, unable to engage in meaningful relationships.

They return home, weary and distant from their parents, spouse, and kids,

Ultimately, finding themselves alone.

In that moment, I turned to my mother, asking, “Is the career truly worth it?”

In response, she shared her own tale.

Though not a physician, she offers much wisdom from her toil,

Working sixty hours a week for nearly three decades,

Juggling multiple jobs, never content to be idle, always ambitious, workaholic.

She takes pride in her precision, her perfectionistic ability to make very few mistakes,

In her ironclad strength and determination to bend reality to her will.

And she excels as a devoted wife and mother as well.

Her story reassures me that marriage and career need not be battling adversaries,

Rather, they are intertwined aspects of a fulfilling life,

A false dichotomy concocted by our minds.

As physicians, we will all face those challenging days at work—

The appointments that run an hour late,

Skipping breakfast, battling traffic,

The backlog of progress notes haunting us.

So what?

Did we enter medicine for fleeting moments of joyful display?

Do we confess to our patients, “I’m not feeling the passion today?”

Or do we lean into our training,

Trusting in the expertise we’ve painstakingly crafted,

Finding meaning in every task,

Even in the mundane act of completing forms?

My mother taught me the latter,

To seek fulfillment in each action, each job,

No matter how trivial it may seem.

To seek satisfaction from your actions,

Rather than expectations of the outcomes of your actions.

Isn’t that what it means to be a true professional?

To be a person who treats their job with the respect it is due,

No matter how unsavory it may be?

This philosophy resonates deeply within me.

It is the essence of Karma Yoga,

The principle that doing your job well is itself a meditative practice.

But why should I believe this?

Like everything else in my life,

I asked why.

Eventually, I found an answer:

So that my patients receive my meticulously crafted care,

Even if that means simply filling out insurance forms,

Ensuring they can afford the treatment they need.

So that I return home, fulfilled by my efforts and the small impact I made,

Free from burdensome thoughts and expectations of how life should be,

With energy to nurture relationships with parents, a future spouse, and eventual children.

So I appreciate life as is.

Thus, the false dichotomy fades away,

And perhaps therein lies the key to true happiness.

Namrata Kantamneni is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

How the Tables Have Turned

by Dr. Coral Matus

Personal Statement:

I wrote this while visiting my daughter, who is a PGY-1 Family Medicine resident. We had dinner plans, but she called to tell me that there was a patient in labor who was “complete and pushing,” so she was going to be a bit late. I had a surreal flashback to the many times I made that call to her; this is the result:

How the tables have turned…

She was a schoolgirl waiting with anticipation for the report from my day. Girl? Boy? Had she guessed correctly?

Did the guessing game help her focus less on the waiting?

Did she realize that I was pursuing my passion, but that didn't mean she was any less important to me?

Did she realize that I struggled almost daily with the guilt of disappointing her or making her sad?

She is a young doctor in training. I wait in anticipation for the report from her day. Girl? Boy? Did I guess correctly?

Praying for her safety, well-being and peace helps me focus less on the waiting.

Knowing she is pursuing her passion makes the waiting worth it.

I pray she feels no regret or guilt for pursuing her dream. I am so proud of her.

Dr. Coral Matus is the Associate Dean for Clinical Undergraduate Medical Education and an Associate Professor within the Department of Medical Education and the Department of Family Medicine at the UTCOMLS

Octogenarian’s Song

Image source: Unsplash

by Dr. Lloyd Jacobs

The aged are driven to the redoubt

where the game is solitaire

and the cards and dice are recollections

The world of youth expands,

apace the universe itself, but the aged

know their world will shrink to nothing.

Not to explore again an urban wilderness

Not to ride again the buoyant sea

Not to know again love’s lubricious feast

We are the housebound, confined where

infirmity destroys. So lay the cards

in suits and play against the fates.

Dr. Lloyd Jacobs is President Emeritus of The University of Toledo. He has published 3 collections of poetry and was previously a professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan

Medicine in the Palm of Our Hands

by Nithya Sundar

Medium: Photography

Dimensions: Aspect ratio 16:9

Artist’s Statement

During a medical mission trip to Guatemala with Dr. Paat and Students for Medical Missions, I was part of a team that provided care to over 700 patients in underserved communities. One case left a lasting impression: a 32-year-old mother of three who presented with right upper quadrant pain radiating to her back. She described the pain as worsening after eating fish. Leading the encounter, I took her history, performed a physical exam, and identified a positive Murphy’s sign. I applied skills recently learned in our GI unit, recalling the population at greatest risk for having gallstones —female, of fertile age, and with an elevated BMI —and applying them in a real-world clinical setting.

As a colleague used a portable point-of-care ultrasound, I captured an image of the screen revealing a gallstone in the patient’s gallbladder. This confirmation of cholelithiasis validated her symptoms and guided her care, exemplifying the incredible utility of real-time imaging in resource-limited settings.

The portability and immediacy of the ultrasound device were invaluable. In a setting with limited access to healthcare, it provided instant visualization of pathology, enabling quick clinical decision-making and eliminating unnecessary delays. This moment underlined the significance of point-of-care ultrasounds—not just as a diagnostic tool, but as a means of empowering providers to deliver compassionate, effective care to those who need it most.

Nithya Sundar is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS

Scraping the Pan for Crumbs of Pound Cake

by Dr. S. Amjad Hussain

This incident happened thirty years ago.

In American hospitals, the operating theaters are totally secluded from the rest of the hospital. It is a world where surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, surgical technicians, and other theater workers share this sanctum sanctorum.

Most operating theaters also have a lounge where, between cases, the staff, including surgeons, take coffee breaks and enjoy whatever snacks are available on a particular day. The nurses and surgical technicians bring these snacks on their own.

On that day, while waiting for my next operation, I went to the lounge to grab a cup of coffee. There on the snack table, I saw a half pan of pound cake. The other half had already been consumed. Pound cake being my weakness, I took a spoon and started scraping residue of the cake from the pan. A nurse came in the lounge and questioned why I was scraping the empty half of the pan rather than helping myself with the cake itself.

It was an Arabian Nights moment. Most stories in that classic start when one character questions another character about a certain situation, and a thread of story within a story begins.

I grew up in a lower-middle-class family in Peshawar. With the sudden death in 1944 of my father, a high-level government official, the family slid down a few rungs on the economic ladder, and our three-square meals became lean and less square. But the age-old custom of hospitality did not change. Guests were entertained with proper tea service and a pound cake, and other delicacies.

The cake I remember was a medium-sized round cake in the shape of a nomad’s round yurt and a dome measuring five or six inches in diameter. It was covered at the bottom and around the sides with thick confectionery paper. The top, like a round mountaintop, was bare. When the guests were done with the tea service, the only thing left was the paper that wrapped the cake. We would snatch the paper and would painstakingly scrape the paper for tiny, small pieces of cake that had stuck to the paper during baking. We could hardly mine a teaspoon or two for our effort. But that was enough to tingle our taste buds.

I told the story to the nurse in the surgery lounge, and she looked sad. She said she had no idea I grew up in abject poverty.

In all honesty, I did not grow up in abject poverty. Compared to some people living in our own town, we were rather well-off. We had adequate food, clothes to cover our bodies, and a roof over our heads.

In so many ways, my story was that of the poet Ibn Insha (1927-1978), who wrote the following short poem, which illustrates the periods of deprivation and affluence in the life of one person. Here is an English translation of the original Urdu poem.

When I was a small lad, with great expectations, I went to a fair. I wanted to have so many things, but my pocket was empty, and I couldn’t buy anything.

Now that those days of deprivation are in the past, the fair is still attractive and enjoyable. If I wish, I could buy every shop in the fair, or I could buy the world.

I don’t have the feeling of deprivation in my heart, but I am not that carefree young boy anymore.

Charles Lamb (1775-1834) was an English writer and essayist. His famous essay “Old China” illustrates the general sentiments that Ibn Insha expressed in his poem. In the essay, Lamb and his sister recall fondly when Charles wore a threadbare suit but could not afford a new one. And how they used to buy the cheapest tickets to the theater and would stand in the pit of the theater to watch the play. But now that they are well off, buying expensive theater tickets did not bring the joy they once enjoyed.

I think the Lambs were recalling my version of scraping crumbs off the pound cake’s wrapping.

The United States is the richest country in the world. One would think that with such affluence, there would be very little poverty in the country. But numbers tell a different story. In America, 11.5% (almost 38 million) are below the poverty level. There is scarcity amidst plenty.

There are men, women, and children who go to bed hungry. It is mind-boggling for many people outside the US to imagine such poverty in America. On the global level, there are more than 700 million people (10% of the world population) who are below the level of poverty. The United Nations defines poverty as someone earning less than $1.90 a day or, in Pakistani terms, a little more than 500 Rupees a day.

A few years ago, while on a trip to the Dominican Republic, I saw an impressive scene on a beach one early morning. Incidentally, the Dominican Republic occupies the eastern half of Hispaniola. Its western part is Haiti, a politically unstable country where poverty is rampant.

Set on the beach was a breakfast table for two. An attendant waited a respectable distance from the table to attend to a young couple’s wishes. On the same island, perhaps less than a hundred miles away to the west, were people eating what the natives call mud cookies to satisfy their hunger. They mix a little salt and cooking oil with the mud and make patties.

I could not comprehend a beachside breakfast luxurious table for two and mud cookies on the same island.

When I compare the poverty of my family with others, I realize, cake crumbs aside, we were definitely better off than many people in the world. Poverty is a relative term. It is a spectrum. My family’s slide on the economic ladder, Charles Lamb’s tattered suit and cheap theater tickets, and some Toledo children going to bed hungry are connected through an invisible thread of scarcity. It is only the matter of degree.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain holds emeritus professorship in cardiothoracic surgery in the College of Medicine and Life Sciences and emeritus professorship in the College of Arts and Letters, University of Toledo. He has been an op-ed columnist for the Toledo Blade and essayist for The Friday Times of Lahore, Pakistan

The Eternal Flame

Image source: Unsplash

by Alisa Chen

What is medicine but a light

Shining through the desperate night?

Though the hounds of death may call

The staff of Asclepius stands tall

Shining everywhere but on itself

Through dust-laden, ancient shelves

Warmth for the sick and wounded

Before their clock strikes twelve

Yes, death is an eternal dusk

On all who walk this mortal plane

Yet it casts no fear on the candle

Burning bright all the same

This scarlet shall never dim

Though it may flicker on a whim

Striving to shine through the veil

Bringing those gone to here and well

History and healers may change

Yet the spirit of sanctity holds its name

Each of us, sworn to fan the flame

Ensure its fire shall flare ablaze

Alisa Chen is a third-year medical student at the UTCOMLS